Advanced tips for using velocity in Sprint Planning in a Scrum Team

As a Scrum Master, when you’re planning a sprint, your Product Owner wants to know how many Story Points (SPs) you can tackle in one sprint. That way, the PO can estimate how many features you can build in that sprint and how long it takes for the team to build them. To understand what you can handle, you can look at the past performance of a team. But how do we measure past performance?

One aspect of this is velocity: the amount of Story Points Done in one sprint. Just be careful not to give this number too much importance when measuring performance, because in the end, performance is more about value, and that’s a lot harder to measure.

So, don’t use velocity to express the quality of the team’s performance. Use it as a tool to determine how much work can be picked up in the next sprint(s) and for roadmap calculations. This prediction is highly dependent on the capacity, i.e. the availability of the team members. During the summer, when 50% of the team is on holiday, we can only do 50% of the work – not a surprise, I’d say. But there are other factors as well.

How can we measure velocity?

It sounds incredibly simple: just take the velocity of the last six sprints and take the average. Unfortunately, it’s not that simple. You have to take a couple of other things into account:

– capacity: more (or less) holidays taken than average

– capacity: people joining or leaving the team

– overflow stories: a bad sprint at the end of the measurement period or a first sprint with a very high velocity will even out when measuring a large number of sprints, but with fewer sprints, it can skew the figures significantly.

So, you start with the Full team velocity. This is your average velocity when your full team is available that sprint. Let’s says it’s 80 SPs.

Then, you have to do some math to take in all the variables. For example, is 50% of your team on holiday? Then your sprint probably needs to be reduced to 40 SPs.

At INFO, we have 30 vacation days per year, so including bank holidays and absences, your team probably runs on 87% of the Full team velocity, resulting in 70 SPs. I would call this the ‘average velocity’. So, if we have a project of 350 SPs, calculations show that it takes us around five sprints, so somewhere between four and six sprints.

Once you’ve calculated your Full team velocity (past performance), you have valuable information that you can use for the Sprint Planning.

Calculating ‘upcoming capacity’ and the effect on the sprint velocity

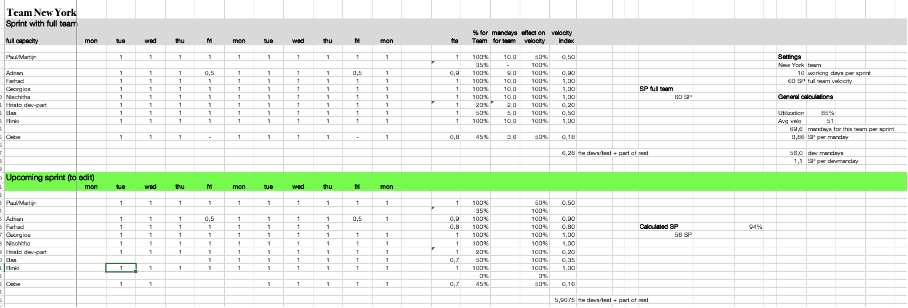

As a math-fan, I changed this first part: together with other team members, we created an Excel sheet where you input the holidays of that sprint (or someone leaving the team) and it will give you a good, calculated velocity. With this calculated velocity, the team looks at impediments and other factors that might influence velocity.

In the end it’s still up to the team to determine the predicted velocity, but the first calculation is now done by Excel. The Product Owner can use this Excel sheet before the Sprint Planning, to calculate the estimated velocity and to get a feeling about which stories can be picked up during the next sprint. You can download this Velocity Excel from our GitHub account.

Overflow stories and the effect on the sprint velocity

In Scrum, we want to deliver value, and a story that is 80% developed doesn’t deliver value yet since it’s not Done. So, when we calculate the velocity of a past sprint, we only look at the stories that are Done.

However, this number doesn’t say enough to accurately predict the velocity for a next sprint. We should take those overflow stories into account as well when predicting the velocity of next sprint, but how?

In the Sprint Planning ceremony, look at the stories that were initiated during the last sprint and are now added to the new sprint. Then, ask the team ‘How many SPs are developed for this story?’ for each story.

Example:

Story 1: 8 SPs of which 7 are developed already

Story 2: 13 SPs of which 11 are developed already

Total: 18 SPs developed

Add those 18 SPs to your predicted velocity: 18 + 70 = 88 SPs and let your team do the final check when filling the sprint with roughly 60 SPs (including those stories that are only partially done). I call these 60 SPs the ‘goal’.

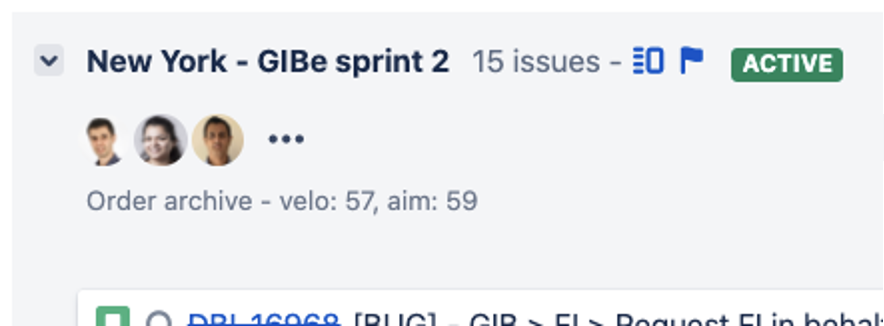

Since I need both numbers and need to distinguish them, I call the predicted velocity of the sprint the ‘velo’ (independent of overflow stories) and the number that includes the overflow stories the ‘goal’. As a PO during Sprint Planning, you fill your sprint with this goal in mind, which your team is probably happy to reach.

Practical tip: In JIRA – a popular tool for managing backlogs/sprints – the PO usually already creates a ‘next sprint’, so I add this velocity number to the ‘sprint goal’-field which makes them show up on the JIRA backlog. I often add the velocity of the next sprint a week before it starts, so the PO gets a feel for the amount of work he/she needs to prepare.

At the start of the Sprint Planning, when we know the overflow stories and have calculated the goal, we add the goal number to that ‘sprint goal’-field, as well.

Impediments, the stories and other factors that might influence velocity

The final part is the stage where the team adds valuable knowledge on possible impediments, the complexity and uncertainties of stories and other factors that might influence velocity (like a training day). This leads to a final set of stories that can be picked up during the sprint.

A well-structured capacity and overflow calculation is a crucial part of the Sprint Planning and asks for dedicated time and attention.

Hopefully you’ve learned how to improve your sprint planning and velocity predictions. Don’t forget to check and recalibrate your Full team velocity every now and then.